Egyptian Priests and Creativity

By Aaron Yodaiken. Initially published .

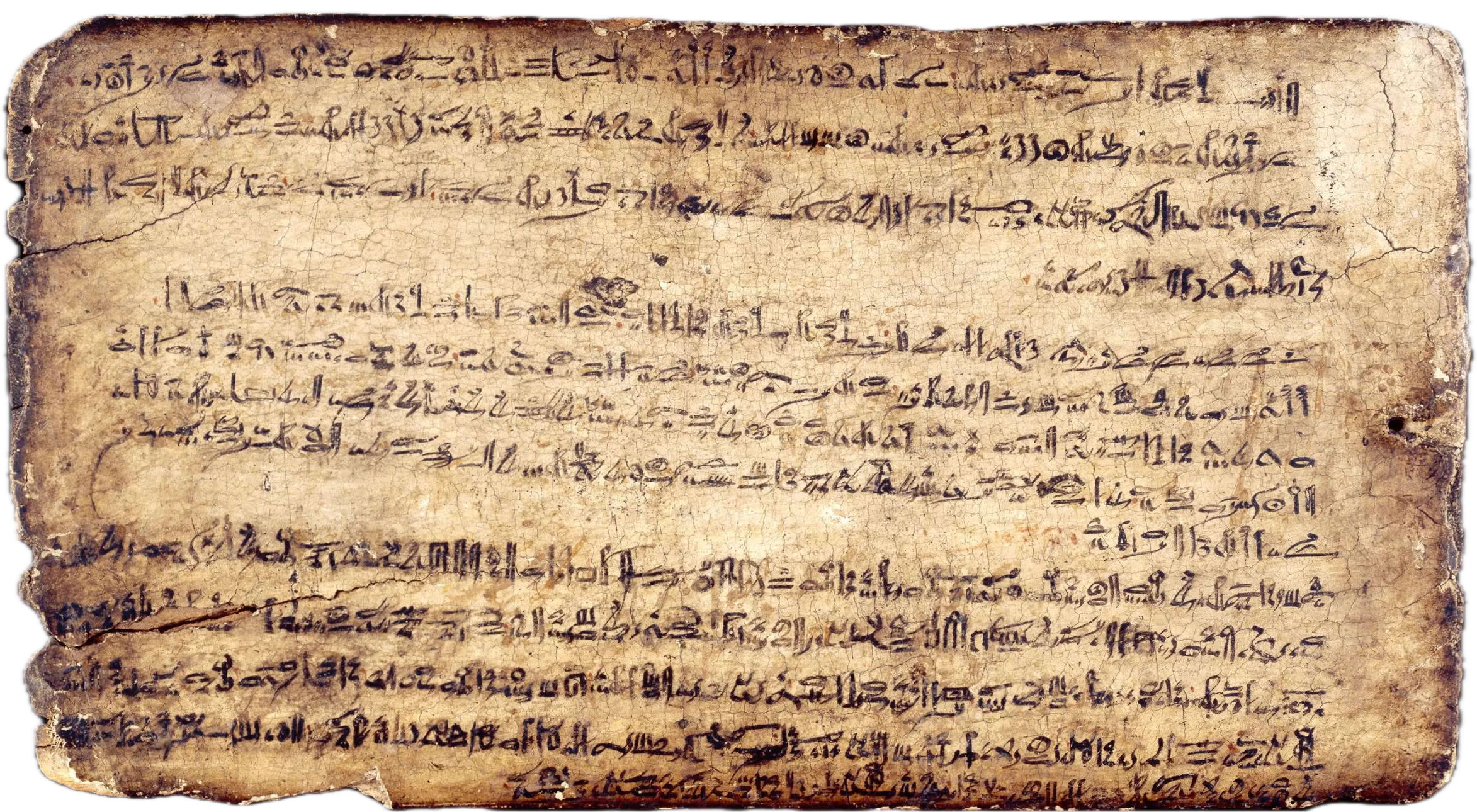

One of my favorite artifacts from the British Museum is this tablet written around 2000 BCE1 by the Egyptian Priest Khakheperraseneb:

The tablet begins with what might be the first recorded creative crisis:

If only I had unknown utterances

and extraordinary verses,

in a new language that does not pass away,

free from repetition,

without a verse of worn-out speech

spoke by the ancestors!

Of course, Priest Khakheperraseneb’s lament of being too late is weakened not by his predecessors but by his successors. One thousand years after Priest Khakheperraseneb, Homer created the Odyssey and the Iliad. Three and a half millennia later, Shakespeare wrote Hamlet. Four thousand years passed before our era’s greats began doing their things.

And, of course, in the many millennia since Khakheperraseneb, many writers have attempted to resolve this tension between creative anxiety and reality. Ecclesiastes axiomatically declares it a fallacy: “there is nothing new under the sun”2. Mark Twain comforted a friend being accused of plagiarism, saying “all ideas are second hand”3. Later on, he would elaborate on this theme, not just defending old ideas but exalting their use4:

There is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope. We give them a turn and they make new and curious combinations.

In the same vein and around the same time, T.S. Eliot wrote that “immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different”5.

The truth in these ideas applies not just to written creativity but to all creativity. Eliot’s line was, ironically, much more famously adopted by the much more famous Picasso as “good artists copy, great artists steal”.

Technology, too, is a creative pursuit, and in technology, too, Twain’s kaleidoscope applies. One of our industry’s greatest creative thinkers, Steve Jobs, quite directly echoed Twain, Eliot, and Picasso when he said that “creativity is just connecting things”. The progress that we see from technology—whether it is manifested in longer global life expectancies6 or productivity growth7—comes not from constant original thinking that Khakheperrasneb yearned for but through ideas stolen and recombined in ever so slightly more efficient ways.

Modern artificial intelligence tools—particularly large language models—so fascinatingly fit into this process. For all the different metaphors about them, I find it most helpful to think of these systems as turning Twain’s kaleidoscope at superhuman speeds, generating combinations a human might never discover. Their ability to process and recombine existing patterns makes them powerful collaborators in the creative process. (Yet—at least for now—they serve best when guided by human judgment, taste, and intentionality.)

There has never been a more interesting time to be discovering and integrating old ideas. As AI keeps getting better and the scope of problems gets bigger, don’t worry about originality. Just as Priest Khakheperraseneb was, we are still so early. Let’s write. Let’s create. Let’s build systems that work for people in ways they haven’t before.

———

Footnotes

-

The British Museum via a friend. Unfortunately, only a small fraction of the Khakheperraseneb’s writing is preserved, but Kadish (via Wikipedia) argues that Khakheperraseneb was a major literary figure. ↩

-

The New Oxford Annotated Bible via Wikipedia ↩

-

The Marginalian via Google ↩

-

The Quote Investigator via Claude ↩

-

The Sacred Wood via a college English class ↩